No. No. No.

No.

No.

Okay, so I’m about half of the way through Doc of the Dead on Netflix (it’s a

little too goofy for its own good, but it has some stunning visuals in its

interlude pieces and it includes fascinating interviews from some very heavy

hitters in the zombie community) and I’m getting really frustrated, so I’m

going to take a few minutes to just vent here.

Cool? Good.

Here’s my problem: Haitian zombies aren't zombies.

There, I said it. They just aren't.

Although

they share a name with the creature introduced and popularized by the works of

Romero (a slow moving, mindless, reanimated corpse that craves human flesh, that multiplies

by killing victims who then become zombies, and that can only be (re)killed by

a direct attack on its brain), the Haitian Vodou zombie should not be confused with zombies as we now

think of them (i.e. the zombies this blog is dedicated to). Despite a few obvious similarities, in most observable ways the

Haitian zombie and the Romero zombie are two separate constructs and, though

linked thematically, should be considered as distinct from one another. Of

course, I'm not implying that we should not refer to Haitian zombies as zombies

(it is THEIR name, after all), but rather that it is necessary to acknowledge

the fundamental differences between the two concepts in order to gain a full

understanding of either.

First, though, let's get

through the apparent similarities: Haitian zombies are people raised from the

dead*, and Haitian zombies are mindless**. That's pretty much where it ends.

And, in both cases, the seeming similarity is undermined in some sense (hence,

the asterisks).

To begin with, *Haitian zombies

are not actually raised from the dead, but rather are raised from the grave.

This qualification, of course, is in reference to the fact that our current

understanding of the Haitian zombie (and even certain early Haitian

understandings), does not identify the zombies as dead but as seemingly dead.

This is indicated as early as W.E. Seabrook's "... Dead Men Working

in the Cane Fields," the short story most responsible for introducing the

Haitian zombie to the popular consciousness. At the end of the story, the

narrator relates a passage from the official Haitian penal code which seems to

offer a non-supernatural explanation for presence of reanimated corpses: "Article 249. Also shall be

qualified as attempted murder the employment which may be made against any

person of substances which, without causing actual death, produce a lethargic

coma more or less prolonged. If, after the administering of such substances,

the person has been buried, the act shall be considered murder, no matter what

result follows" (Seabrook 49). However, whether working under this

seemingly more rational explanation, or the folkloric understanding of the

zombie as "a soulless human corpse, still dead, but taken from the

grave and endowed by sorcery with a mechanical semblance of life [...] a dead

body which is made to walk and act and move as if it were alive,” the

Haitian zombie is a corpse that "came from the grave" (Seabrook

41). Which, on the surface, is a bit of a nitpicky distinction, but it

signifies nonetheless. In both cases, Romero and Haitian, it is the newly dead

(or apparent dead) who return. However, in Haiti, it is exclusively corpses

that have been buried that are revived while in Night it is exclusively

those bodies that have not been buried that return. The latter indicates an

interruption of the proper death rites. The former, however, gestures to a

willful violation of death itself (more on the Bokor later).

To begin with, *Haitian zombies

are not actually raised from the dead, but rather are raised from the grave.

This qualification, of course, is in reference to the fact that our current

understanding of the Haitian zombie (and even certain early Haitian

understandings), does not identify the zombies as dead but as seemingly dead.

This is indicated as early as W.E. Seabrook's "... Dead Men Working

in the Cane Fields," the short story most responsible for introducing the

Haitian zombie to the popular consciousness. At the end of the story, the

narrator relates a passage from the official Haitian penal code which seems to

offer a non-supernatural explanation for presence of reanimated corpses: "Article 249. Also shall be

qualified as attempted murder the employment which may be made against any

person of substances which, without causing actual death, produce a lethargic

coma more or less prolonged. If, after the administering of such substances,

the person has been buried, the act shall be considered murder, no matter what

result follows" (Seabrook 49). However, whether working under this

seemingly more rational explanation, or the folkloric understanding of the

zombie as "a soulless human corpse, still dead, but taken from the

grave and endowed by sorcery with a mechanical semblance of life [...] a dead

body which is made to walk and act and move as if it were alive,” the

Haitian zombie is a corpse that "came from the grave" (Seabrook

41). Which, on the surface, is a bit of a nitpicky distinction, but it

signifies nonetheless. In both cases, Romero and Haitian, it is the newly dead

(or apparent dead) who return. However, in Haiti, it is exclusively corpses

that have been buried that are revived while in Night it is exclusively

those bodies that have not been buried that return. The latter indicates an

interruption of the proper death rites. The former, however, gestures to a

willful violation of death itself (more on the Bokor later). |

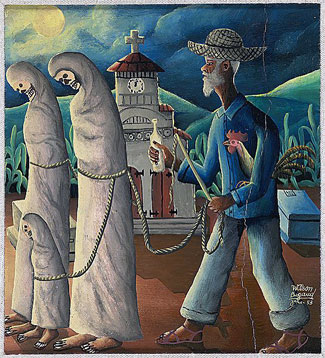

| Zonbi, by Wilson Bigaud, 1939 |

Next, although, for people like

zombie connoisseur John Skipp the tragic truth about Haitian zombies is

that "they [are] slaves. Either raised from the dead to do some vile

master's bidding, or somehow mesmerized into mindless subservience, zombies

were the husked-out shells of humanity, whose sole purpose was to do the

degrading shit no willful soul would do. In that sense they were the ultimate

slaves, in that they had no will of their own," ** Haitian zombies are not

actually mindless (Skipp 10). Though the same could be said of the zombies

in Night of the Living

Dead - who try car door

handles, use basic tools, shield their eyes from branches, and demonstrate basic self-preservation skills in

avoiding fire - the Haitian zombie is un-mindless in a very different way.

Not only

are they capable of far more intricate tasks (reaping sugar cane is not an easy chore), but they are actually

able to follow orders. This indicates a level of receptive communication that

the Romero zombies simply lack. This is decidedly not a trivial distinction;

the Haitian zombie is defined by its tractability, the Romero zombie by their inability to be controlled. Where the Haitian zombies are literal

slaves, the Romero zombie is a slave only to its appetite. These are very clear

indications of the stark differences in cultural anxieties between the two

societies that created these very distinct monstrous figures. To grossly

oversimplify, one fears being controlled, one fears being out of control.

|

| Know what sucks? Doin' this. Photo: Sean Smith |

(I just realized that Haitian

zombies and Romero's both shamble very similarly in a way that is not readily

undermined in any demonstrable way. So there's that linking them, I guess. In

the immortal words of Deep Blue Something, "Well, that's the one thing

we've got").

To be continued...

No comments:

Post a Comment