Lit:

Novels-

World War Z, by Max Brooks

Although there are several films featuring zombies

that I think have or will become considered part of the overall Western Canon –

Night of the Living Dead and Dawn of the Dead are already part of the

National Film Registry, while 28 Days

Later and probably even Shaun of the

Dead likely to end up on the list eventually (at some point I should

probably seriously consider the fact that the two most well-regarded films of

the Zombie Renaissance are both British films) – there are far fewer written

zombie texts whose places are so secure. If I could only pick one zombie book

or story to nominate for the Canon at large, it would be Max Brook’s World War Z. Though I’m hesitant to call

it a novel (which I admit is probably splitting hairs), Brook’s

mock-ethnography draws on the work of Studs Terkel to provide readers with a “look

back” at the origins of a zombie outbreak in a time and reality not too distant

from the ones they know. That’s actually selling Brooks short; his book reads

horribly horribly true. Which is a bit surprising given its highly satirical

approach (though it could be convincingly argued that the book is parody,

allegory, pastiche, or even all of the above, as well). However you choose to

categorize World War Z one thing is

clear: the book is Max Brooks’s scathing critique of the world as he knows it.

And it turns out, he knows it pretty well.

Traditionally, zombie narratives to be relatively

local affairs. What would a zombie outbreak look like here, where “here” indicates some specific place and time (a rural

farmhouse in the 1960s, millennial London, etc.)? While most of these texts at

least imply that their particular iteration of the outbreak spans the globe (or

will soon if it doesn’t already), World

War Z is the first text that explicitly engages with the global nature of

the pandemic. This serves two purposes. First, it allows Brooks to criticize everybody. Brooks is certainly extremely

critical of late capitalism and the Western military-industrial complex, but

these are hardly the only institutions to draw his withering gaze. Using a

surprising breadth of knowledge regarding geo-politics and world culture,

Brooks takes shots at, well, the whole world for what he regards as a universal

inability to prevent or manage a cataclysm on this scale. Second, but along the

same vein, situating his particular version of the zombie apocalypse as a

global event allows Brooks to destabilize all of the imagined communities to

which we so fervently cling. Zombies don’t respect borders, or faith, or class,

or race, or politics, or gender, or sexual orientation, or any of the other

ways we choose to group ourselves off from one another. By positing zombies as

an Other for all of humanity, Brooks

erases some of the lines between us, leaving a single, human Self. Of course,

whether what’s left is worth saving is another question entirely.

Also, someone please make this into a series. Without

meaning in any way to disparage or denigrate the wildly uninteresting,

dumbed-down, and sterilized action blockbuster that shares its name, World War Z is simply not a story that

is very well suited for film (even if the studio heads hadn’t decided to dip a

good idea in glitter and deep fry it). However, a World War Z TV series, or even mini-series, told in flashbacks by

an enthnographer and his or her interviewees (a similar structure has worked

well in The Wonder Years and, more

recently, How I Met Your Mother),

would be pretty effing amazing. And I’m going to keep harping on it every

chance I get until someone does the right thing and makes it happen.

Other-

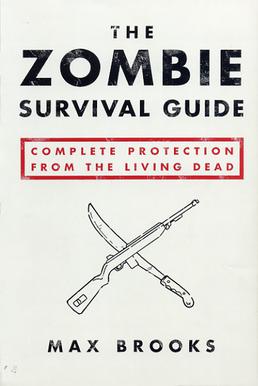

The Zombie Survival Guide: Complete Protection from the Living Dead, by Max Brooks

I really

don’t know what the hell to call The

Zombie Survival Guide, as far as literature goes. I mean, it’s very clearly

a parody, and a high level one at that, but how do you categorize a fictional

field manual? Well, whatever you call it, it’s great, and its impact on 21st

century zombie lit. is undeniable. Continuing the trend that began with the Resident Evil series, and spread to film

with Resident Evil and 28 Days Later, The Zombie Survival Guide showed that zombie books could be both

interesting and financially successful (working its way onto The New York Times Best Seller’s list).

It also helped pull zombies out of what had become a fairly goofy horror/gore niche.

Although it deals, often quite explicitly, with horrific material and even some

gore, The Zombie Survival Guide is

not a horror book. Rather, it uses horror as a tool (along with parody) to poke

fun at how wildly unprepared our pampered society is for any high level

disaster. We don’t even have basic preparedness, let alone “protection from the

living dead.” But Max Brooks is really bright and rarely operates on only one

register. So, while he is clearly parodying survival manual with pitch-perfect

tone and satirizing Western privilege, he also uses his “Recorded Attacks”

vignettes (gestured to throughout the book, and then expanded upon in an

appendix at the end) to raise some really clever epistemological concerns over

the certainty we tend to ascribe to history and how readily we believe the

things we are told by the people we hold as experts. By mixing completely fictionalized

accounts of history with other legitimate but inexplicable historical events

(the chronicles of Hanno the Navigator or the disappearance of Roanoke Colony,

for example), Brooks forces his readers – well, the ones who are paying

attention – to question not only what they “know” but how they know it.

No comments:

Post a Comment